Harry E. McCracken was born on May 16, 1922 in Westmoreland City, Pennsylvania, to Frank and Cora McCracken.

After completing 4 years of high school, Harry volunteered to enlist in the Marines. Before it was administratively acted, his draft notice arrived and was ordered to report at Camp VanDorn, Miss. on January 4, 1942. He was attached to the 99th Division where he was trained as a medic and served with the Regimental Aid Station of the 395th Infantry Regiment. Two years later, Harry and his unit were on the front, in Belgium. His main task was to supply the four forward aid stations of his regiment with the needed medical equipment. On December 13, 1944, the 395th Infantry had two battalions involved in the diversionary attack of the 2nd Infantry Division focused at the strongpoint of Wahlerscheid, in the heart of the West Wall. On December 16, after three days of bitter fighting, all US troops around Wahlerscheid were withdrawn because of the German all out counter attack.

“… our Headquarters Aid Station was in Rocherath. We had set up in a home on the outskirts of the town and by the 18th of December, we were receiving many casualties and some D.O.A. [note : Dead On Arrival] as well. That evening, an attempt to move the bodies back to the Graves Registration area on litter jeeps was unsuccessful, so we returned to our station and placed them alongside our station house in neat rows… »

« … We had a roomful of injured men and we attempted to make them as comfortable as possible by giving injections of morphine to control their pain. Later, during the night, a Lieutenant from the 2nd Infantry Division stopped by with his patrol and he asked why the injured had not been evacuated. I told him that the ambulance drivers had reported that all the access roads were blocked toward the west. He then instructed us to load up all the injured and that we would try to get them through to medical units behind our lines. We did as instructed but I never knew whether they made it or not…”

By this time, the situation had worsened. Armored units of the 12 SS Panzer Division had broken through the forest and were fighting their way into the twin villages of Rocherath-Krinkelt.

“… The next morning we received orders to move out and we loaded our vehicles with equipment and supplies and headed toward the 395th Headquarters Company… the road was heavily shelled and many of us opted to follow the vehicles on foot. By this lime, it was late afternoon and the shells kept coming. While walking along this rural road I heard a shell coming in and I hit the ground. It landed nearby, took two skips along the ground, came to a stop and never exploded…”

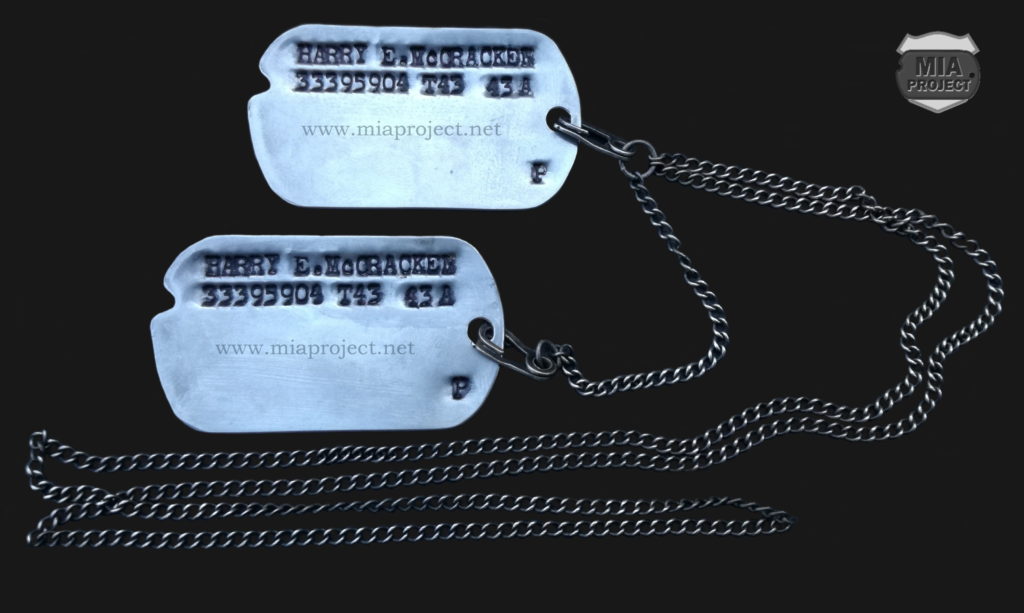

Dog tags worn by Harry McCracken during his time in service (donated by H. McCracken to the MIA Project collection)

By the time Harry and his companions reached the Headquarters area, the trucks were already in convoy and ready to leave. They hopped on the nearest vehicle and headed cross country. The ride was short because the truck bogged down. They all jumped off and resumed walking. Not knowing where they were and where to go, they just walked in the direction they were told to go.

“… Having not arrived at our destination by dark, it was necessary to find a place to spend the night. We came upon a dug-out about 12′ x 12′ and 3′ deep, covered with logs and tin. It looked great to us at the time and we shared the protection it provided for the remainder of the night. The next morning … we all left and began walking once again. We came upon a U.S. Army truck that had some C-rations on board … they were frozen solid but we ate them as if they were good. As we approached a village [note : Elsenborn] we saw a 6×6 truck approaching with a red cross flag flying from the front bumper. It turned out to be our Headquarters Medic truck looking for me. Interestingly, I was MIA for a period of one night That’s OK, I needed the rest… »

By December 19, the 395th had retreated to Elsenborn and established new positions. Harry continues: “…The truck driver took me to a house where our aid station was located, at an intersection of the road from Elsenborn to Bütgenbach. No sooner had we settled in when we were told that German tanks were coming up the road from Bütgenbach toward Elsenborn. The house had a small fruit cellar with a window facing the road. Someone had left a bazooka and some shells in the Aid Station and WaIter Pawlaski (from Minneapolis MN) and I decided to go to the cellar and from the vantage point that the window presented, fire the bazooka shells at the tanks when they approached. Medics were not allowed to carry weapons and we were a little short on expertise in the use of the bazooka, but we felt inclined to take some action in the face of oncoming tanks. We were greatly relieved to learn later that the tanks were stopped before they could proceed to our location. An officer came down into the cellar and asked what we were trying to do and we explained our plan to him. He may or may not have been amused at our bravado, but he told us that if we had fired the bazooka in those close quarters, the concussion could have done a lot of damage to us. So much for stopping a German Panzer column in its tracks!! … »

« … Shelling continued to be heavy and it was suggested to our CO, Capt James Fyvie (from Manistique Ml) that we were in a very vulnerable location,that the Germans were zeroing in on our intersection with great accuracy. He said he would look for a better location for us and promptly left. On his return, he informed us he had found a likely place for the Aid Station in a very sturdily built school house a short distance away. We lost no time in packing everything up once again and moving into the new location. It resembled a fort, was well built with thick, stone walls. And a lucky move it was for two days later a shell made a direct hit on the house we had formerly occupied… »

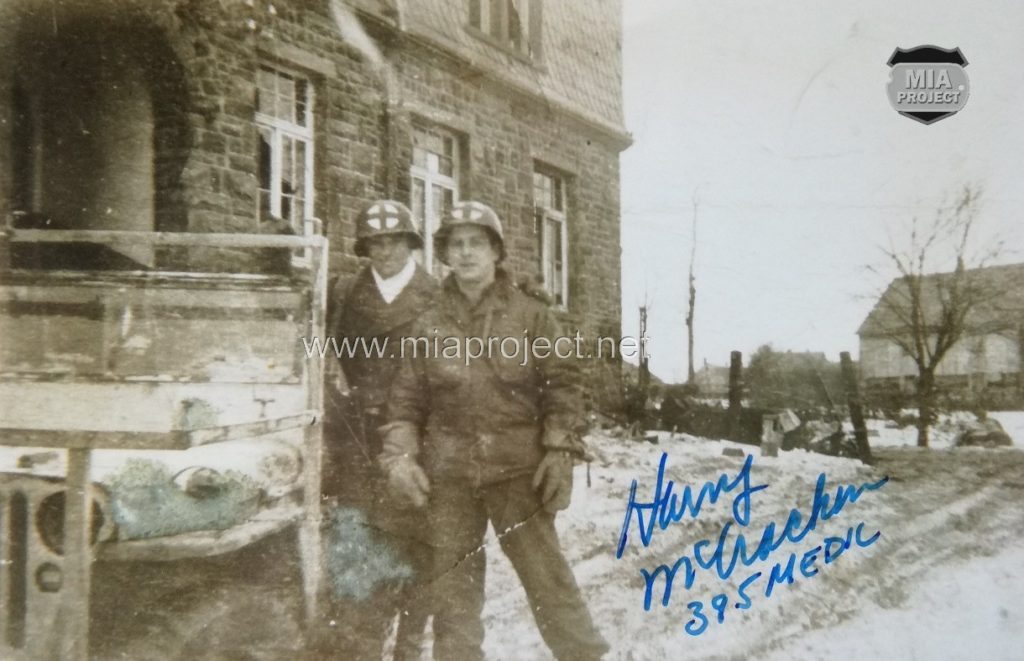

Elsenborn Dec 1944. 395th Regiment HQ medics in front of the school house . Harry is standing far right.

The school house was surrounded by a sea of mud but indeed did look sturdy. It had a concrete floor in the basement and the medical personnel slept there because it provided the best protection. Since the front entrance faced the German lines, they used the side door of the building.

As the medics settled in, the weather worsened, became colder and snow fell intermittently. Harry and his companions used two rooms in the building. The first room nearest the side entrance was the medical room and the second room was the overflow room, which contained a pot belly stove with a smoke pipe sticking out the window. Whenever possible, the GI’s would come in out of cold to warm up at the little stove and snatch a little sack time. Rags were placed over all the windows to maintain black-out conditions.

“ … One night I smelled smoke…” remembers Harry “… and to my surprise saw that some GI had stoked up the fire, making the stove pipe red hot, setting the rags over the windows on fire. Guys were sleeping on the floor all around. There was very little water so after getting the guys out of the room we beat out the flames with whatever we could grab. In a room where we were not allowed to smoke a cigarette in order to keep any light from showing, we had flames shooting out the window! This was not lost on the Germans, because we took a few shells, as a result of this breach of our blackout protocol… »

« …We had many casualties coming in from Elsenborn Ridge, many with frozen feet. Replacements were in short supply during this time so we did not evacuate the injured as readily as previously. If a GI could use a weapon, he was not sent back for further treatment but expected to join his outfit as soon as possible. On the 24th of December, Joe Manor and I were going back to Malmedy for medical supplies and water. En route we were strafed by a German fighter plane at an intersection and our jeep was hit and totally demolished. The water cans were shot full of holes and an MP was hit in the shoulder as he was directing traffic at the intersection. I went back to take care of him. After he was bandaged and cared for, and afoot once again, we set out toward our Aid Station. As I slogged along, my right foot felt squishy, and I looked down to discover I had a flesh wound in the lower calf and blood was running into my boot… »

« …Alter bearing our story back at the Aid Station, Capt. Fyvie decided I should be evacuated for treatment of my wound. My thought was that he was a doctor and could take care of me where I was. Later on when pieces of the bullet began coming out of my leg, he again wanted to send me back to a medical field hospital. I refused for a second time. I received a Bronze Star for providing care for the injured MP before attending my own wound. Truth to be known, at the time I had not yet discovered I was wounded!!! As the war progressed all combat Medics were awarded the Bronze Star. So I had two… »

******************************

Dr James H. Fyvie, physician and surgeon, practiced in Manistique, Michigan, since 1936 after graduating from Rush Medical School of Chicago University and completing his interneship at Harper Hospital in Detroit.

Dr James H. Fyvie, physician and surgeon, practiced in Manistique, Michigan, since 1936 after graduating from Rush Medical School of Chicago University and completing his interneship at Harper Hospital in Detroit.

On September 25, 1942, he was commissioned 1st Lieutenant in the US Army Medical Corps and left Manistique for Camp Joseph T. Robinson, AK. One month later he was assigned to the 395th Infantry Regiment of the 99th Division then in training at Camp Van Dorn, a swampland of southwestern Mississippi. On April 30, 1943, after a short leave home, he received his notice of promotion to the rank of Captain.

As regimental surgeon of the 395 th Infantry, Capt Fyvie distinguished himself during the Battle of the Bulge and was promoted to Major at the beginning of the German campaign. At war’s end, he had been awarded a Bronze Star for meritorious service and a Silver Star for heroic action during the Danube crossing. He returned to Manistique after the war and resume practicing. He also became mayor of Manistique. He eventually retired in 1978. Dr Fyvie passed away on May 24, 1983 at age seventy six.

*******************************

Trips continued to be made back and forth to Malmedy for supplies and it was Harry’s job to supply all four of the 395th infantry Regiment’s aid stations. “…There was an ample supply of plasma for transfusions, however, it is supposed to be transfused at body temperature. This was impossible. The plasma came packaged in a kit with needles, lines and in powder form. The powder had to be dissolved in a bottle of saline solution before it vas administered intravenously. Nothing stayed warm on the Elsenborn Ridge and it was a challenge to try to warm the plasma. We tried to keep the plasma warm by placing the bottles in a pan of water that sat on a little gasoline burner. The bottles stayed there until we went out in the field, then we carried the saline bottles in our arm pits to maintain their warmth… »

Spring 1945. The whole aid station team. Harry 3rd from left center row, Capt Fyvie first left kneeling.

« … After transfusing one GI with several liters of cold plasma, he looked a hopeless case. We placed a blanket over him because we thought he was dead. After a time we saw movement under the blanket and we hurriedly transfused him, again, loaded him in an ambulance and sent him back for further treatment. Working near the front lines, we sent the wounded back as soon as possible and seldom ever knew whether they recovered. I have often wondered about that one.

While we were at Elsenborn, we received our first shipment of penicillin. It came to us as a powder that had to be reconstituted with normal saline. Previous to this time sulfa was the only drug we had to fight infections. Shortly after Capt Fyvie had been promoted to Major, he became very ill and was running a high fever. He decided to try the new medicine on himself right then and there. It worked like the miracle drug that it was. It made believers out of all of us… »

The weather worsened and the Army issued Weasels, a more suitable vehicle with tank like tracks for maneuvering in the snow. Men promptly set about white-washing them in the hope of becoming invisible to the Germans when they were out.

“…We didn’t use the triage system during this time. We had about 12 medics, a doctor and a dentist in our outfit to take care of all the incoming wounded. We treated other ailments such as colds, diarrhea, upset stomach as well as shrapnel wounds, bullet injuries, combat fatigue and frozen feet. There was a big controversy over trench foot as opposed to frozen feet. Our aid station personnel received official notice that GI’s in the field developed trench foot because they did not wash their feet and change to clean socks each day. We were instructed to designate the condition as « trench foot » which was considered a self inflicted wound. Major Fyvie told me that we never were to use those two words on an evacuation card! Although we saw all types of injuries some of the saddest patients to see were those suffering from combat exhaustion. I went to a house one day and found a GI seeking protection by trying to dig into the floor with his fingers… »

“… We remained in the school building until the break out from Elsenborn in late January at which time we headed back toward the cities of Krinkelt and Rocherath. My experience in treating these soldiers seemed like a routine job to me at the time. I was able to accept the responsibility without it creating any lasting personal problems. Of course there were times when patience grew thin but a good night’s sleep and some decent food took care of those times. We were always hungry for fresh meat and we butchered a cow and a pig during our stay at the school house. We greatly enjoyed the meat for as long as it lasted… We had four aid stations and we received three bottles of liquor per day to be used for medical purposes. There was scotch, cognac and some cheaper brands but I was usually accused of keeping the best for our aid station. I should have documented the liquor distribution, for I really tried my best to divide it fairly and I thought that I did. Ironically, I didn’t even drink liquor!

« … Usually the wounded men and the others who needed our help did not complain excessively or give us a hard time. I feel honored to have served as a medic in the 395th and shall always remember and admire the courage and inner strength shown by men on the Elsenborn Ridge…”

Harry served with his outfit until VE Day, receiving the Combat Medic Badge, a Purple Heart, two Bronze Stars and treating more wounded. After remaining briefly in occupation duty, he came back to the States on January 4, 1946, exactly three years after he was drafted.

He was quartered at Fort Indiantown Gap for a few more days and was officially discharged on January 9, 1946.

Harry worked for the Westinghouse Electric Corp in East Pittsburgh and continued to serve as member and former chief of Westmoreland City VFD, a life member of Penn Township Rescue 6, on the Penn Township Youth Commission, was a Medicare Counselor, was a longtime volunteer for Meals on Wheels. Harry joined the 99th Infantry Division Association and served as president and Archive Chairman. He played a key role in the creation of a 99th exhibit in the Soldiers and Sailors Museum in Pittsburgh.

Harry worked for the Westinghouse Electric Corp in East Pittsburgh and continued to serve as member and former chief of Westmoreland City VFD, a life member of Penn Township Rescue 6, on the Penn Township Youth Commission, was a Medicare Counselor, was a longtime volunteer for Meals on Wheels. Harry joined the 99th Infantry Division Association and served as president and Archive Chairman. He played a key role in the creation of a 99th exhibit in the Soldiers and Sailors Museum in Pittsburgh.

After a long life of service, Harry McCracken passed away on May 2, 2018 at age 95 in Walden’s View Personal Care Home. He rests at Brush Creek Cemetery, Irwin, PA.

Sources:

Interviews and letters with Harry McCracken

Photos MIA Project collection – courtesy Harry McCracken and M. Lorquet