Scranton, Pennsylvania

506th Fighter Squadron

404th Fighter Group

I. Historical background

December 26, 1944 – Roetgen, Germany

There was a guttural hum in the distance as the American column snaked through the Belgian border hamlet of Petergensfeld and the adjoining German town of Roetgen. The hum quickly grew to a roar. At an altitude of 2,000 feet, American fighter-bombers zoomed over Roetgen.

Captain Ollie O. Simpson’s fifteen-plane 506th formation had broken off minutes before. Guided by ground controllers, the four « Pintail » flights began searching for targets along the German side of the border. For his part, First Lieutenant Robert G. Fenstermacher, a veteran of fifty-four combat sorties, was flying number 3 in Captain Anderson’s yellow flight.

Someone in the flight pointed out what seemed to be enemy vehicles. Fenstermacher glanced down and spotted the column. Following his Yellow Leader, the twenty-three-year old pilot turned his ship on her wingtip, dropped the nose, and opened the throttle. The 2,500 horsepower Pratt & Whitney engine screamed as the plane hurtled downward. With the added weight of three 500-pound bombs, airspeed increased, and the big bird’s controls stiffened. He made a quick rudder correction to align his gun sight on a truck.

Muzzle flashes pulsed along the leading edge of each wing. Streams of spent casings tumbled from beneath the aircraft. Bullets kicked up dirt on the road and peppered the truck. Fenstermacher yanked back on his control stick and climbed. Despite white stars on the vehicles and desperate waves from horrified ground troops, the American planes made a strafing pass. It was now 13:15, the day was clear with just a low ground haze .

First Lieutenant Kenneth Cobb, flying in Yellow Four position that day, rejoined Fenstermacher within seconds. The Texas native recalls:

« … Our flight made one pass on the vehicles and after rejoining, I noticed that Lt Fenstermacher still had all three of his bombs. I still had my belly bomb. Lt Fenstermacher called and said he was going down on the target again. I never saw him start his pass for just as he called, I broke away for another target. I didn’t see him again. »

« … Our flight made one pass on the vehicles and after rejoining, I noticed that Lt Fenstermacher still had all three of his bombs. I still had my belly bomb. Lt Fenstermacher called and said he was going down on the target again. I never saw him start his pass for just as he called, I broke away for another target. I didn’t see him again. »

The sky was cluttered with turning, diving and shooting aircrafts. Roetgen was a busy place. In American hands and considered an entry point into Germany, it held a fuel depot and the 78th Infantry Division command post. Guns of the 552nd Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion protected the depot and command post. The battalion had quad fifties and 40-mm Bofors guns. This time, on the ground, the U.S. troops were ready to return fire. An M51 gun carriage mounted with a “quad fifty” sat along a hedgerow. When Fenstermacher started his dive, the gun crew let go with their four 50-caliber machine guns. Other crews joined in. Hundreds of tracers, lurid reddish fireballs, crisscrossed the sky.

One of the fireballs struck the engine compartment of Fenstermacher’s machine. Bullets stitched the plane’s aluminum skin and a halo of pale orange flames enveloped the fuselage. The P-47 maintained its diving angle and rolled over before hitting the road. Plane and pilot disintegrated in a giant ball of smoke laced with flames.

The « Jug » exploded in front of the Petergensfeld house #25 occupied by the Noel family. The detonation of the three bombs rocked the little brick building, and burning aviation fuel set it alight. Fortunately, Alere Noel and her two daughters had sought refuge in their cellar after the first attack. They managed to escape the house when it started to burn.

Soon after Fenstermacher hit the ground, American soldiers searched the crash site. There was a huge hole in the road that obstructed traffic. One of the first to arrive was Second Lieutenant Carroll Ross of the 552nd AAAW Bn.

“…I watched the plane from the time it started to dive until the time it crashed. The pilot didn’t bail out of it. While searching in the remains of the aircraft engine, I dug out one identification tag bearing the name Robert G. Fenstermacher, O-818531, and also a piece of officers’ forest green shirt. At the time all that remained from the pilot’s body were two objects that resembled fingers and a small piece of spinal cord. These were amidst the glowing embers and were burning at the time. I turned the dog tag and the piece of shirt over to the commanding general of the 78th Division within an hour of the crash.”

Other soldiers arrived and poked at the burning wreckage with sticks. They found a mangled limb and a skull fragment. The men placed these pieces in a linen sack for evacuation. What happened to them afterward remains a mystery. Were the body parts received by the Graves Registration Service or did they disappear in the turmoil of the battle? If they did reach a U.S. cemetery, were they mistakenly buried as an unknown soldier?

Fenstermacher’s unit initially reported him as missing in action. The army later changed his status to killed in action after investigators collected Lieutenant Ross’s statement and those of other eyewitnesses. None of the eyewitnesses believed anything remained of Fenstermacher beyond the few pieces recovered just after the crash. In 1950, an army board deemed Fenstermacher’s remains “non-recoverable.”

II. Renewed Interest

After the successes of the MIA Project in 2001, Bill Warnock continued his effort to collect information and regularly drove to the National Archives. Besides missing 99th Division soldiers, he researched missing servicemen from other units that fought alongside the 99th. This included airmen.

Among them, Warnock discovered Fenstermacher and his controversial “non-recoverable” status. The missing aircrew report for Fenstermacher shed light on the crash. His individual deceased personnel file added more clarity, but the exact location of the impact crater remained vague.

Warnock visited Petergensfeld in 2004 and discovered the houses had been renumbered after the war and many more since built. The following year he located a possible 1945 aerial photograph of the hamlet. The image was at the National Archives among records of the Defense Intelligence Agency. He returned to the archives in 2006 and confirmed that Petergensfeld was indeed shown in the photo. He forwarded his findings to Seel and Speder for further investigation. Hopefully they could now pinpoint the Noel house and the impact crater. It was reasonable to expect that the site still held human remains, remains driven into the ground by the impact and protected from the fire.

But there was an obstacle. The MIA Project team needed a partner with the expertise and financial resources to excavate a crash site. There were no immediate candidates. That changed in early 2011 when Mark Noah of History Flight contacted Warnock.

The two groups met that May and agreed to cooperate on several unresolved cases that offered the potential for success.

III. Search & Recovery

2011 – Site Reconnaissance

Seel and a German-speaking colleague reconnoitered Petergensfeld several times before finding the Noel house. Seel became acquainted with Klaus Löhrer, present-day owner of the house. Löhrer knew about the crash and was enthusiastic to cooperate. He mentioned that U.S. Government representatives had visited him several years earlier, but no action had ensued.

In June 2011, Seel, Speder, and Warnock escorted a History Flight team to Petergensfeld. The primary task was to identify the aircraft type and determine if remains of the pilot could still be in the ground.

Metal detectors located a large, deep target in a drainage ditch along the road in front of Löhrer’s property. A quick probe in the ditch revealed a sizeable piece of crumpled aircraft aluminum. Smaller parts emerged in an empty lot nearby. One of these aluminum bits bore a part number. It was a stringer fragment from the right wing of a P-47.

Archeologists Gus Pantel and Kent Schneider of the History Flight team operated ground penetrating radar (GPR) which detected large subsurface anomalies under the road as well as under Löhrer’s front lawn. Cadaver dog “Buster” and his handler Paul Dostie searched the entire site. Buster was trained to detect human decomposition chemicals. Those included chemicals produced by human bone as well as cremated human remains. The dog alerted several times in the vicinity of the subsurface anomalies.

The site merited thorough excavation.

2012 – Recovery Operation

Preparation for the recovery operation involved frequent contact with the local police and town authorities. Permits and permissions had to be secured. The site excavation was set for August 2012.

When the excavation began, MIA Project members Seel and Speder were busy assisting JPAC at another crash site (see Hunconscious story) and played only a minor role at Petergensfeld. Author and researcher Danny Keay joined History Flight for the Fenstermacher recovery. Keay had led the recovery of P-47 pilot Paul Mazal in 2005. Extra help came from German Army Reservists.

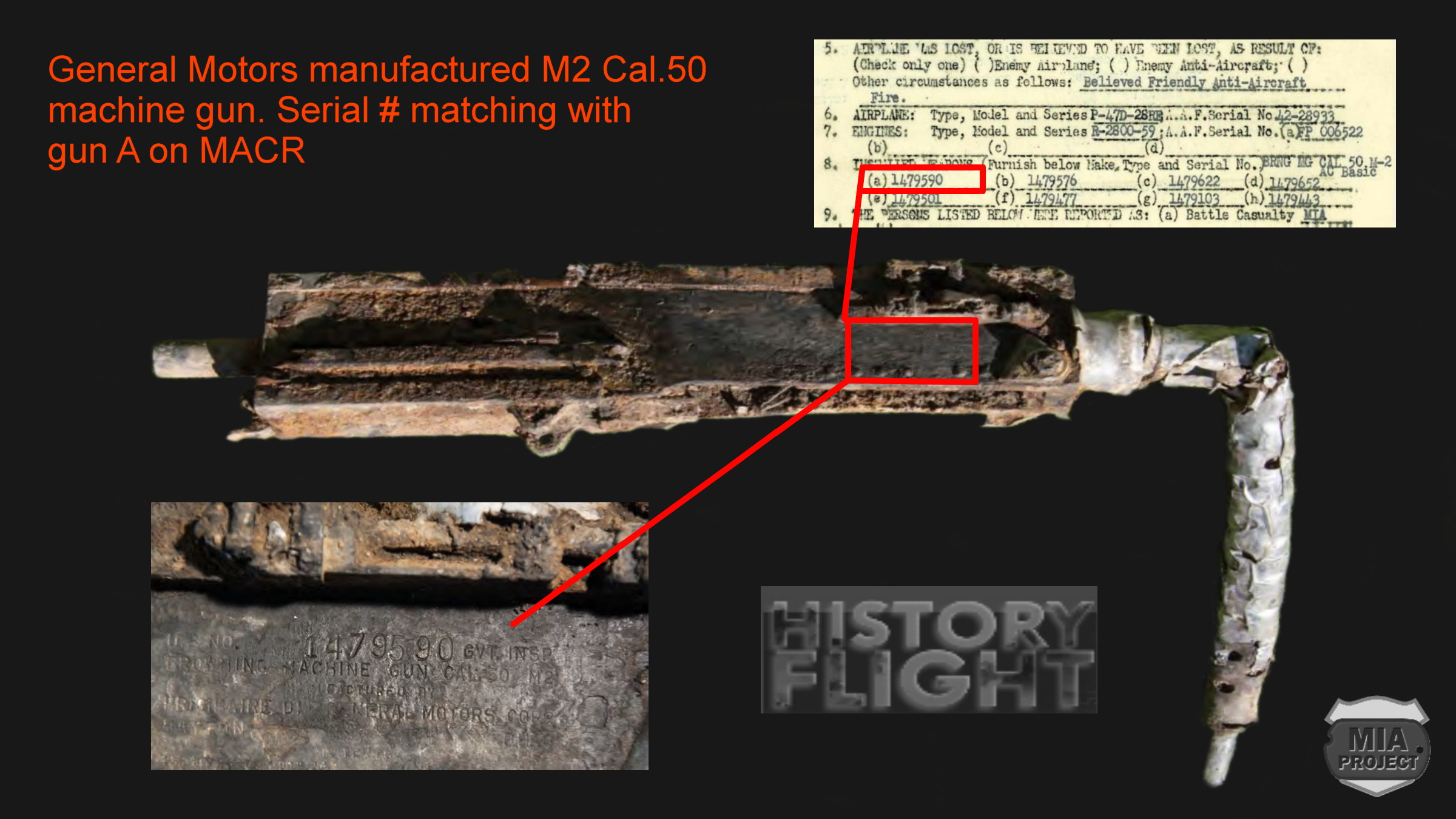

Mark Noah and the History Flight team laid a grid over Lörher’s front yard. In the very first unit, just below the surface, the team found remnants of life support equipment. Three feet down, two molars appeared. Both teeth were in perfect condition and had fillings. These were consistent with Fenstermacher’s dental records. In adjacent units, the team recovered shoe soles, uniform shreds, a signet ring, parachute buckles, as well as several ribs and long-bone fragments. A large concentration of 50-caliber ammunition lay below the hedge separating Lörher’s property from the drainage ditch. The first machine gun appeared soon afterward. A total of five guns surfaced. The serial numbers of four matched the recorded left-wing armament of Fenstermacher’s P-47. The other gun and its serial number matched one of the four right-wing weapons.

The largest subsurface anomaly turned out to be the huge Pratt & Whitney motor. It lay three meters (ten feet) below the ditch. The weight of the motor and the force of its impact had compressed the clay layers in which it was embedded, making removal difficult. The local authorities dispatched a backhoe and personnel to help extract the engine.

After five days on site, History Flight turned over the human remains and material evidence to the local police. The JPAC team leader at the other crash site took custody of the remains and artifacts the following week. There were a total of three teeth and over seventy bone fragments.

Two members of History Flight returned in September to process soil contaminated with petro-chemicals from Fenstermacher’s aircraft. The local government had stored this hazardous material at a municipal facility. The soil yielded fourteen more bone fragments and additional artifacts including part of a photo locket. Perhaps the locket had once held a picture of the pilot’s wife.

Sixty-seven years after losing his life, Robert Fenstermacher no longer lay abandoned in an unmarked grave. Teamwork made this possible. It was an effort fueled by a tireless determination to bring home the fallen and provide answers to their families.

For his part, Klaus Löhrer plans to use aircraft wreckage to construct a memorial. It will be a tribute to the young pilot who fell from the sky at the hands of his own countrymen.

IV. Final Interment

The U.S. Government positively identified First Lieutenant Robert G. Fenstermacher on April 30, 2013. Bob Fenstermacher, the pilot’s nephew, selected America’s most sacred ground, Arlington National Cemetery, as the place of final interment.

On October 18, 2013, History Flight, represented by Paul Schwimmer and Mark Miller, MIA Project members Bill Warnock, JL Seel, JP and Sonia Speder, joined the Fenstermacher family for a funeral with full military honors. Klaus Löhrer and his wife Monika also attended.

The flag-draped casket was borne to the grave site on a gun caisson drawn by six magnificent white horses from the “Old Guard,” a tradition dating to the Civil War era and reserved for officers and Medal of Honor recipients. On this bright and cloudless  day, the cortege stood behind the caisson when a History Flight owned B-25H flew over the cemetery. John Makinson piloted the aircraft and offered a fitting tribute from an old warbird to a fallen warrior.

day, the cortege stood behind the caisson when a History Flight owned B-25H flew over the cemetery. John Makinson piloted the aircraft and offered a fitting tribute from an old warbird to a fallen warrior.

Bob Fenstermacher Jr, the pilot’s grand-nephew, read a eulogy. Chaplain Scott Kennaugh conducted a graveside service. In an adroit, well-practiced drill, the casket team folded  the American flag into a triangle and presented it to the next-of-kin on behalf of the President of the United States. The ceremony concluded with three rifle volleys and the haunting notes of « Taps ».

the American flag into a triangle and presented it to the next-of-kin on behalf of the President of the United States. The ceremony concluded with three rifle volleys and the haunting notes of « Taps ».

Almost seventy years after leaving his native Pennsylvania to serve his country, First Lieutenant Robert G. Fenstermacher rests now among his brothers in arms, plot 60 grave 10353.

Addendum: Besides Fenstermacher, one other member of the 506th Fighter Squadron died on December 26, 1944. First Lieutenant Clinton Winters Jr. of Hayti, Missouri, belonged to the Blue Flight led by First Lieutenant Carl Parsons of Florida. Winters’ ship named “Rae” was also hit by ground fire, perhaps American. He kept his plane aloft and crashed minutes later near Mechelen, Holland. He is interred today at the Netherlands American Cemetery.

Sources:

MACR 11992

Lt Robert G. Fenstermacher – IDPF

Photos: courtesy Bob Fenstermacher & Klaus Löhrer

MIA project collection