By JP Speder

642nd Bomb Squadron, 409th Bomb Group

2Lt Lynn W. Hadfield – Pilot – Salt Lake City, UT.

2Lt Lynn W. Hadfield – Pilot – Salt Lake City, UT.

Sgt Vernon L. Hamilton – Gunner – Monongahela, PA.

Sgt John Kalausich – Gunner – Charleston, WV.

I. Historical background

March 21, 1945 – 11:03

At first it was a distant rumble. It soon turned into a loud roar as they appeared in sight. All around, air raid sirens started wailing. Without hurry, civilians left their activity and proceeded to their raid shelters. In the country, farmers had built their own raid shelter beside their house. Most of the time, it was a trench covered with logs and dirt. Four or five steps were bringing them 6 feet underground, where they sit on a bench or simply on the floor. They couldn’t stand, it was just big enough for a family. Air activity above the Dortmund area was intense in the spring of 1945 and March 21 was just another day.

In Hülsten, a hamlet a few miles south east of Reken, locals went to their shelters. Eight year old Heinrich Vestrick and his father were standing at the edge of the forest. From their prone position, they could plainly see the bombers coming. Too late however to reach the security of the hamlet shelters.

On the ground, anti aircraft gunners were preparing their guns feverishly. Intense air activity meaning intense anti aircraft opposition, the area was peppered with all sorts of Flak batteries. Not far away from Reken was a battery of four big 128mm guns. The biggest caliber available for Flak guns.

Nine thousand feet higher, two boxes of A-26 bombers of the 409th Bomb Group were on their way to the target – a railroad marshalling yard at Dulmen, 10 miles to the east.

A USAAF photographer captured the fatal moment when the Invader of Lt Cotton was hit in the left wing.

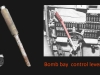

Deployed in two boxes, they had taken off two hours earlier from airfield A-70 located at Laon-Couvron, France. The village of Reken was their initial point. As the first bombers started to open their bomb bays, Flak opened up and soon saturated the sky with black mushroom like clouds. A-26’s in the first box started to bounce around as if in rough and turbulent air.

Flak gunners were accurate that day and immediately hit the right of the first box. Ship #322359 (D6-L), piloted by Lt Donald J. Cotton, took a direct hit in the left wing. The plane flipped on his back and plummeted down. Soon after another A-26B, ship #322353 (D6-G), flown by 2Lt Lynn W. Hadfield left the formation. Seemingly untouched, the Invader slowly rolled on its back and disappeared.

Lt Col Lewis W. Stocking, the commander of the 642nd Bomb Squadron, was a few hundred yards behind. He recalled:

-“… I was flying in number seven position in the second flight of the first box. On the bomb run, while we were receiving very accurate Flak, I saw number two airplane of the first flight receive a direct hit. There was a brilliant red flash, the left wing was torn off and, together with the debris, the airplane immediately disappeared from the formation. I didn’t watch him down, but during the time the airplane was within the field of vision, I didn’t observe any parachute…

-“… I was flying in number seven position in the second flight of the first box. On the bomb run, while we were receiving very accurate Flak, I saw number two airplane of the first flight receive a direct hit. There was a brilliant red flash, the left wing was torn off and, together with the debris, the airplane immediately disappeared from the formation. I didn’t watch him down, but during the time the airplane was within the field of vision, I didn’t observe any parachute…

… Approximately ten seconds after the above plane was hit, I observed the number five airplane turn sharply out of formation to the right. The aircraft rolled almost on its back on its turn and disappeared from view, going down in what considered to be an uncontrolled dive. I did not observe any parachutes from this aircraft. Both were hit before bombs away. Upon return to the field, I found that the pilot of the number two aircraft was Lt Cotton and the pilot of number five airplane was Lt Hadfield.

F/O Stuart K. Gibson was flying in the second flight :

-« … Just a few minutes past the Initial Point, before opening our bomb-bay doors, I saw Lt Hadfield’s ship peel up to the right. It fell over on its back and headed straight down toward earth. I was a mile or two behind him at the time. I didn’t see his plane hit by Flak. The last I saw of the plane, the bomb bay doors were closed and I saw no parachute leave the plane.

Aboard the same Invader, Sgt Richard E. Tucker, also witnessed the agony of Lt Hadfield’s ship.

-« …I was flying as Engineer Gunner in the aircraft flying in the number 5 position of the first flight, second box. Lt Hadfield was number five, first flight, first box. On the bomb run, before the bomb-bay were opened, I happened to glance at Lt Hadfield’s plane and saw it peel up with the left wing up. It then kept going and turned over on his back while nosing down. I kept the plane in my view until we passed over it and then lost sight of it altogether. To the best of my knowledge no parachutes opened … »

From their prone position at the edge of the forest, Heinrich and his father saw both planes falling down. There were no parachutes. If Cotton’s plane hit the ground way out from them, the other A-26 crashed at the edge of their hamlet, in a pasture bordering a farm.

“ … I saw the plane coming down vertically…”, remembers Heinrich, “… and hit the ground with a muffled explosion. My father told me to stay where I was and ran towards the plane. As he approached, there was one big explosion and ammunition started to go off. I started to cry as I thought my father had been killed, until I saw him emerging from the smoke …”

After the raid, German soldiers came over to check the crash site but there was nothing to see but a six foot deep smoking crater and twisted plane parts. The next day, other soldiers loaded the bigger parts in several army trucks and moved away. The area fell into American hands the following week and the farmer soon filled the crater.

Lt Lynn W. Hadfield (r) and Sgt John Kalausich pictured with their A-26 on January 16, 1945 (Courtesy Collin Turner).

Post war investigations located Lt Cotton’s A-26. Cotton and the observer, S/Sgt Don E. Nord were recovered. Unfortunately the remains of the gunner, S/Sgt Loring E. Lord were never recovered and he is still unaccounted for.

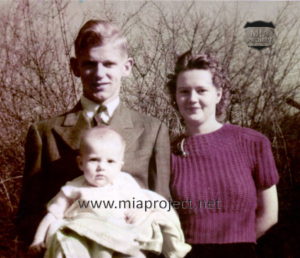

2Lt Hadfield’s ship, #322353, alas, was never located and the crew declared officially unrecoverable in 1951. The twenty-six year old Salt Lake City native pilot left a wife, Betty, and two children, Kent and Mary Ann. His gunners, Sgt Vernon L. Hamilton and Sgt John Kalausich, devastated mothers and sibling.

Recovery operations

The general area of Dulmen had seen an important air activity in February and March of 1945. In 2010, Peter Monasso, director of the AVOG crash museum in the Netherlands was working on air combats over the area gathering information on a missing pilot of the Royal Canadian Air Force. He published a note in the local newspaper asking for help and for witnesses. Local history buffs stepped forward to join the search effort and one of them, Adolf Hagedorn, joined the group with several files. One of them was Lt Hadfield’s ship. Adolf and his friends were no rookies. Over the previous years they had worked and identified about 60 crash sites, both allied and Germans, in the Haltern am See area.

In 2011, the group did important research work on a B-26 shot down over the area in March 1945, as well as on the two A-26’s of the 642nd Bomb Squadron. Unfortunately, the crash site of Lt Hadfield’s plane was not located. Their research work was forwarded to the JPAC (Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command) who dispatched a team to visit the two sites located. Their conclusion was that there were not enough evidences to start a search operation. Despite JPAC reluctance to launch recovery operations, Adolf and his friends continued to work on those cases and remained in contact with History Flight. Over the following years, JPAC sent several teams back to the sites but nothing took place. Moreover, JPAC historians strongly believed that Lt Hadfield’s plane had crashed in Holland trying to head back home. This seemed to be the end of the story.

Five years later, in the summer of 2016, a new element will revive the hope. A friend of Adolf Hagedorn was playing cards in a local Inn. One of the players attending was Heinrich Vestrick. As the game was going on, the conversation merged to old war stories. Heinrich then mentioned the US twin engine ship he saw falling down. Adolf was notified and this triggered his curiosity as the location was unknown to him. A meeting was quickly organized and Heinrich led Adolf’s team to the site. A search with metal detector revealed Douglas manufactured pieces. Since the crash site of Lt Cotton’s plane was known, this new location should be the place where Lt Hatfield’s ship had crashed.

Information was immediately forwarded to History Flight and the DPAA (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Command – new agency replacing JPAC). The crash site was located in a private owned pasture next to a farm in the hamlet of Hülsten. It was important to act quickly as there was a construction project underway right where the crash site was located. On September 6, 2016, a team of DPAA reconnoitered the site and granted a recovery mission. The owner of the pasture also granted permission to dig his land if the excavation was completed for the end of December.

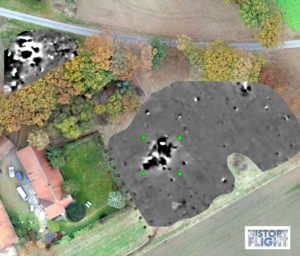

The first elements of History Flight arrived on site on November 18, 2016, and under the leadership of anthropologist David Rankin, started to search the perimeter. A previous GPR scan of the pasture realized by HF archaeologist Chet Walker had located three areas of particular interest. David Rankin, former JPAC anthropologist, was assisted by Roland Wessling, MSc in forensic archaeology and anthropology with a large experience in international atrocity crime investigations. Roland was leading a Cranfield Forensic Institute immediate response team of the Cranfield University, UK. Roland was also known as being one of the two senior archaeologists of the team that excavated 250 New Zealand and Australian soldiers from a WWI mass grave in Fromelles, France, in 2009.

Rankin and Wessling focused on the main area, supposedly the crater, while the Belgian team of the 99th Division MIA Project flagged the boundary of the debris field using metal detectors. The search of the debris field itself yielded poor results. One of the three selected targets revealed a post war trash pit. The owner also confirmed that over the decades, he had removed every piece of metal emerging from the ground for the well being of his horses. He also showed the location of an old raid shelter where plane parts and human remains were supposedly buried after the crash. There too, the search yielded nothing but building debris, bricks and junk. The attention of the whole team then focused on the crater. A sandy and rather soft soil was a pleasant surprise for digging and sifting operations. Over the ensuing days and weeks, plane parts, life support equipment and human remains surfaced.

Of particular significance a data plate reading “US Army Air Corps – Type A-26B serial 43-22?53”, a damaged fountain pen cap reading “L W Hadf…”, one dog tag belonging to Lt Hadfield, both dog tags of Sgt Kalausich, Sterling silver pilot wings – not named but worn by Lynn Hadfield, a Balfour 10k gold ring engraved with “VLH” (for Vernon L Hamilton). Besides, life support and personal equipment such as parachute fabric and buckles, portions of Flak jackets, fragments of US Army issued shoes, buttons and leather flying helmet, a cal.45 pistol and different French and US coins. A large number of bone fragments and several teeth were also recovered.

Of particular significance a data plate reading “US Army Air Corps – Type A-26B serial 43-22?53”, a damaged fountain pen cap reading “L W Hadf…”, one dog tag belonging to Lt Hadfield, both dog tags of Sgt Kalausich, Sterling silver pilot wings – not named but worn by Lynn Hadfield, a Balfour 10k gold ring engraved with “VLH” (for Vernon L Hamilton). Besides, life support and personal equipment such as parachute fabric and buckles, portions of Flak jackets, fragments of US Army issued shoes, buttons and leather flying helmet, a cal.45 pistol and different French and US coins. A large number of bone fragments and several teeth were also recovered.

By December 20, 2016, thanks to a clever leadership, decent weather conditions and an unwavering team work, the site was cleared. Three airmen, abandonned where they gave their last full measure of devotion, were on their way home.

After a long wait of nearly two years, Lynn Hadfield, Vernon Hamilton and John Kalausich were officially accounted for on December 13, 2018.

John Kalausich was buried in Tyler Mountain Memorial, WV, on February 23, 2019.

March 19, 2019 – The American Airlines airplane carrying the remains of 2nd Lt. Lynn W. Hadfield passes under a water salute at the Salt Lake City International Airport. (courtesy Deseret News)

Our team was fortunate to attend the funeral of Lynn Hadfield in Sandy, Utah on March 21, 2019, exactly 74 years after he died tragically over Germany. A large attendance gathered at the Utah Veteran’s Cemetery & Memorial Park where a solemn and moving ceremony took place.

Vernon Hamilton was buried in Monongahela, PA, next to his mother, on April 14, 2019.

After seventy four years in an isolated grave, the three men were returned to their families to find a proper and decent resting place.

Blue skies and tail wind gentlemen.

Sources:

MACR 13230

Lt Lynn Hadfield, Sgt Vernon Hamilton & Sgt John Kalausich – IDPF’s

Conversations with Adolf Hagedorn.

Interviews of Heinrich Verstick (via Adolf Hagedorn).

History Flight contingent:

Mr Mark Noah History Flight Director & Project Manager

Mr David Rankin Recovery leader/ Anthropologist

Mr Roland Wessling Assistant recovery leader/Anthropologist

Life support technicians:

Mr Jean-Louis Seel

Mr Julien Seel

Mr Jean-Philippe Speder

Recovery specialists:

Mr Adolf Hagedorn

Mr Sascha Weltgen

Mr Danny Keay

Mr P J Dermer

Dr Steve Cassells

Mr Chuck Thudium

Ms Julia Bauer

Ms Aundrea Thompson

Ms Marina Tinkcom

Mr Charlie Enright

Ms Sadie Ann Ries

Ms Bethan Boulter

Ms Benedetta Mammi

Ms Claudine Abegg

Mr David Brown