By JP Speder

599th Bomb Squadron, 397th Bomb group.

1Lt William P. Cook – pilot – Alameda, CA

F/O Arthur J. LeFavre – Co-pilot – Red Bank, NJ

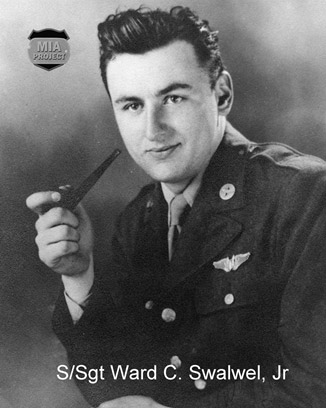

S/Sgt Ward C. Swalwel, Jr – Radio-gunner – Chicago, IL

S/Sgt Franck G. Lane, Jr – Engineer- Top turret gunner – Cleveland, OH

S/Sgt Maurice J. Fevold – Tail gunner – Chicago, IL

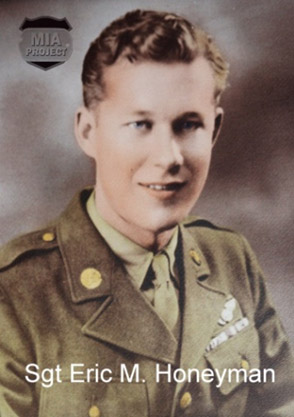

Sgt Eric M. Honeyman – Toggler – Alameda, CA

I. Historical background

It was about 09:10 on this cold Saturday morning, December 23, 1944, when the last B-26 bomber left the base at Péronne France. The 4000hp of the two Pratt and Whitney R-2800 engines painfully lifted “Hunconscious”, the B-26G piloted by First Lieutenant William P. Cook of Alameda, California. Within minutes, she climbed to her cruising altitude and joined thirty-three other planes of the 397th Bomb Group for the day’s mission, an attack against a railroad bridge spanning the Moselle River at Eller, Germany.

The group flew in a two-box formation and followed a pathfinder aircraft and three “Window” aircraft. The latter carried no bombs and had the task of releasing strips of aluminum chaff to disrupt radar-controlled antiaircraft guns. The pathfinder carried four 500-pound bombs. The other planes each carried four 1,000-pound bombs. They flew for an hour over friendly territory before reaching the frontline city of Malmedy, Belgium. The airmen circled the city and took a course toward their objective. Enemy antiaircraft batteries immediately engaged the formation which was visible from the ground. At 10:20 AM, German gunners scored two hits. Sergeant McGinnis, a top-turret gunner, described the results. “Right off the bat, Flak got a ship in the right engine. She went over on her back. … Another blew in half.” Both victims came from Box II, the trailing box.

« Blind Date » crew in July 1944. Standing L to R are Lt Turner (pilot), Lt Cook, then co-pilot, Lt Livelburger (Bombardier) and S/Sgt Matthews (radio gunner). Kneeling are Frank Lane (Navigator / top turret) and Maurice Fevold (tail gunner). Turner completed his tour late July and returned to the US. Lt Cook succeeded as pilot. LeFavre, Honeyman and Swalwell completed the vacant positions. Note that Clinton Matthews was killed on that same 23rd December mission while flying aboard another B-26 shot down by a FW190. (courtesy Lane family – Brian Gibbons ).

The first plane lost was “Hunconscious”, Lieutenant Cook’s ship. Hit in the right engine, torque from the good motor pulled the machine into a snap roll. It then plummeted down toward earth. Cook and five other men perished.

Seconds after Flak hit Cook, a shell struck Lieutenant Charles W. Estes ship, “Bank Nite Betty”. The deputy box leader and his crew described the incident during their post-mission debriefing. “Three minutes after Malmedy, aircraft 144 hit at about top turret and split in half. … No chutes seen.” All seven men aboard Estes’s aircraft died.

After losing Cook and Estes over Belgium, the 397th pressed ahead into German airspace and began the bomb run despite continued Flak. The aircraft jettisoned their explosives at 10:37 AM, bombing on the pathfinder’s mark. They hit the bridge. The formation made abroad left turn and headed toward home. Then disaster descended. Luftwaffe fighters pounced on the Americans. Aerial combat raged for ten minutes before P-47s intervened and broke up the attack. Flak and fighters claimed eight bombers over Germany. Only five planes returned to France without damage. Four of them were no longer airworthy and requiring months to repair. December 23, 1944, constituted the worst single-day losses for the 397th: ten aircraft downed, forty-five men dead, and twenty-one men prisoners of war. The group later received a Distinguished Unit Citation for destroying the Eller bridge.

After hostilities ended, the American Graves Registration Command accounted for thirty-nine of the dead. Lieutenant Cook and his crew were the only ones missing. The American Battle Monuments Commission later inscribed their names on the Wall of the Missing at the Luxembourg American Cemetery.

II. MIA search

Decades later, during the 1990s, German aviation researchers began investigating the loss of Cook’s aircraft. The missing aircrew report contained little information regarding the circumstances of its disappearance. The report offered speculation that the aircraft fell somewhere in the geographic area where Luftwaffe fighters attacked the bombers. After years of work, they pinpointed nine 397th crash sites. Only one was in Belgium. This was the crash site of “Bank Nite Betty”, Estes’s aircraft. The plane had broken in two pieces while at altitude. The forward fuselage landed in a cow pasture southeast of Allmuthen, Belgium. The two German researchers thought the tail section had landed nearby, a belief that would eventually prove false.

During their research, they determined that antiaircraft fire had struck two 397th aircraft over Belgium, and both went down. The researchers knew that Estes had piloted one of them. Who piloted the other one? There was only one possibility—Cook. But where exactly did he crash?

In the autumn of 2006, the picture became clearer thanks to a German forestry worker affiliated with an organization called the Airwar History Working Group Rhine-Moselle. He had learned about the spot where the tail of Estes’s aircraft was supposed to have crashed. There was an impact crater. He searched in the vicinity and discovered over one hundred pounds of aircraft wreckage and shreds of U.S. Army Air Force clothing, including a leather fragment from the collar of a B-3 winter flying jacket. It bore a laundry mark, H-7489.

The Air War History Working Group identified the wreckage as being from a B-26. More importantly, they determined the laundry mark had no relation to anyone aboard Estes’s aircraft. The mark instead related to Cook’s bomb toggler, Sergeant Eric M. Honeyman (ASN 39037489) who also hailed from Alameda, California. This revelation led to an expanded search at the site in November. British-born aviation researcher Danny Keay joined the effort, and the group discovered more artifacts and two long-bone fragments.

The Air War History Working Group identified the wreckage as being from a B-26. More importantly, they determined the laundry mark had no relation to anyone aboard Estes’s aircraft. The mark instead related to Cook’s bomb toggler, Sergeant Eric M. Honeyman (ASN 39037489) who also hailed from Alameda, California. This revelation led to an expanded search at the site in November. British-born aviation researcher Danny Keay joined the effort, and the group discovered more artifacts and two long-bone fragments.

Keay and the Germans contacted the U.S. Army Memorial Affairs Activity-Europe (USAMAA-E). In December 2006, two representatives from that organization arrived on site, conducted an investigation and took possession of the bone fragments and other artifacts. USAMAA-E deferred the case to the Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) for immediate action. Two JPAC historians visited the site in early 2007 and reported there were enough evidences “to warrant further investigation.”

Years rolled by. Despite the discovery of Honeyman’s flying jacket and meaningful bones, no recovery operation occurred. History Flight, a US non-profit organization, became involved in 2011 after developing a relationship with members of the 99th Division MIA Project. Bill Warnock, the project leader and his Belgian team mates Jean-Louis Seel and Jean-Philippe Speder had twenty years experience searching for missing soldiers of the 99th Infantry Division, having recovered twelve of them. The crash site lay on the periphery of the 99th sector and was well known to the Belgian-American group.

History Flight partnered with the group, and together they reconnoitered the crash site in June 2011 and found the area untouched since 2006. The task was going to be difficult. The site had been harvested years before and was now covered with a bush like vegetation. Moreover, the crater had been filled with branches and discarded logging cuttings. Seel and Speder extended the search on site in the Fall and unearthed many meaningful evidences, including equipment worn by crew members but no remains surfaced. This led to a larger operation in April 2012 which History Flight funded. Under the guidance of three American archaeologists, the consortium surveyed the site, pulled forest debris from the crater and drained its water for the first time in over sixty years. Buster, a cadaver dog attached to the Mammoth Lake Police Department in California, was also present to detect the potential presence of human decomposition chemicals. The team found more evidence identifying the specific B-26 model, a model consistent with Cook’s ship and not Estes’s. The team also recovered human remains and reported this to JPAC, USAMAA-E, and the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO).

JPAC had now no other option than facing up to its responsibilities and dispatched forensic anthropologist Derek Benedix to the site. He examined the remains and recommended that JPAC conduct an immediate excavation of the crater and adjacent terrain. The first JPAC team arrived on site in May and began what proved to be a huge recovery operation. Beside the crater and its immediate surroundings,  the debris field extended deep into a forest. A sizable quantity of human remains were eventually recovered as well as personal belongings, all consistent with the missing crewmen.The first element to surface was Sgt Honeyman’s dogtag. More were unearthed as the number of excavation

the debris field extended deep into a forest. A sizable quantity of human remains were eventually recovered as well as personal belongings, all consistent with the missing crewmen.The first element to surface was Sgt Honeyman’s dogtag. More were unearthed as the number of excavation  units augmented. Cook’s ID bracelet and dogtag, Swallwel and Lane’s dogtag and LeFavre’s bracelet and shoes were recovered. Unidentified but meaningful objects also came to light. Beside a Sterling silver pilot wing badge in pristine condition, a torn officer’s cap badge, English and French coins, a lighter, a fountain pen were among personal effects. Of particular significance an intact Elgin manufactured A-11 watch that had frozen the time of the crash. 10:25.

units augmented. Cook’s ID bracelet and dogtag, Swallwel and Lane’s dogtag and LeFavre’s bracelet and shoes were recovered. Unidentified but meaningful objects also came to light. Beside a Sterling silver pilot wing badge in pristine condition, a torn officer’s cap badge, English and French coins, a lighter, a fountain pen were among personal effects. Of particular significance an intact Elgin manufactured A-11 watch that had frozen the time of the crash. 10:25.

Long before th e Belgian-American coalition started to work on this project, they had established contact with family members of Lieutenant Cook’s crew, including the sister of Ward Swalwell, a Chicago native and waist gunner aboard “Hunconscious”. When Jackie learned that her brother’s probable resting place had been located, she decided to visit the spot with her family. Escorted by 99th MIA Project members, they toured the site, met with JPAC team, and attended an improvised memorial service at the site. JPAC’s mission ended on September 17, 2013 after six recovery teams rotated on site. A total combined surface area of approximately 6400 square yards was excavated to an average depth of one foot.

e Belgian-American coalition started to work on this project, they had established contact with family members of Lieutenant Cook’s crew, including the sister of Ward Swalwell, a Chicago native and waist gunner aboard “Hunconscious”. When Jackie learned that her brother’s probable resting place had been located, she decided to visit the spot with her family. Escorted by 99th MIA Project members, they toured the site, met with JPAC team, and attended an improvised memorial service at the site. JPAC’s mission ended on September 17, 2013 after six recovery teams rotated on site. A total combined surface area of approximately 6400 square yards was excavated to an average depth of one foot.

III. Final salute

In a memorandum dated July 22, 2014, JPAC confirmed the positive identification of the six crew members and notified the families.

Maurice J. Fevold was buried in Badger, Iowa, with full military honors on October 20, 2014. More than four miles of flags lined both sides of the street leading to Blossom Hill Cemetery for the soldier’s funeral procession.The Badger Fire Department also parked fire trucks along the route, and the Iowa Air National Guard provided a KC-135 plane that flew over the service.

William Parker Cook, the 27 year old aspiring surgeon and pilot of Hunconscious, had left his medical internship to enlist in the Army Air Forces. Just before going overseas, he had married his fiancee, Jean Swanson. He was buried in Mountain View Cemetery at Oakland, California, on October 26, 2014.

Frank G. Lane, Jr found his final resting place in Willoughby, Ohio, on May 2, 2015.

Eric M. Honeyman, although raised in California and enlisted in the Army Air Forces, was of Canadian origin. He was not granted to access US citizenship because he had not reached the legal age of 21. Eric’s parents, Bella and Eddy, had both donated their bodies to science, so there is no graves. The family decided to bring him home. Eric Honeyman was buried next to his grand parents in Trail, British Columbia, Canada, on June 22, 2015.

The last two crew members, co-pilot Arthur J. LeFavre and radio gunner Ward C. Swalwell, Jr were buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia. LeFavre and a second casket containing unidentified osseous remains of the crew members were buried on August 18, 2015. Ward Swalwell was buried next to them two days later, on August 20, 2015.

99th Division MIA Project members William C Warnock, Jean-Philippe Speder and Jean-Louis Seel, History Flight, represented by Paul Schwimmer and his wife Audrey, joined the families and relatives of the six crew members. After a short funeral service held at the Old Post Chapel of Fort Myers, the flag draped casket with the unidentified remains of the six men was carried to the grave site by an artillery caisson drawn by six magnificent white horses. The horse escort and the caisson are reserved for officers and Medal of  Honor recipients. LeFavre and Swalwell were placed in hearses and transferred to the grave site. After a brief eulogy, casket teams of the « Old Guard » folded the American flags in triangle with their unique, perfect and ceremonial drill. The chilling notes of « Taps » and a three rifle volley concluded the ceremony.

Honor recipients. LeFavre and Swalwell were placed in hearses and transferred to the grave site. After a brief eulogy, casket teams of the « Old Guard » folded the American flags in triangle with their unique, perfect and ceremonial drill. The chilling notes of « Taps » and a three rifle volley concluded the ceremony.

Abandoned in a Belgian forest for nearly seventy one years, Lt Cook and his crew found a final resting place befitting with the measure of their sacrifice.

Sources:

MACR 11985

Lt Cook, F/O LeFavre, S/Sgt Swalwel – IDPF’s

S/Sgt Lane, S/Sgt Fevold, Sgt Honeyman – IDPF’s

Preliminary report – Danny Keay