Sam Lombardo was born in the tip of the Italian boot, in Caraffa del Bianco, Calabria, on July 12, 1919. At the time, life in rural Italy was tough. The only way to escape misery and hard work was to move out to the industrial regions of northern Italy or leave for America or Australia.

In 1926, Pietro, Sam’s father, immigrated to the United States and settled in Altoona, Pennsylvania. Macon and hard worker, he sent money back to his wife in Italy and prepared the coming over of his family.

« …We were one of the few families in town, Sam remembers, who could afford to wear shoes, and only because Dad was in America and sending money back to us… »

In the ensuing years, fascism spread throughout Italy, and oppression by Mussolini’s Black Shirts increased political tensions. Sam had received two flags. One was a Social Party red flag, symbol of Italian workers. The other was an American flag, symbol of liberty, sent by his father. « I didn’t know what the red flag meant, Sam continues, but I knew the beautiful American flag was the flag of our future – America. » Both flags became illegal and the family hid them. With a husband in America, Agata, Sam’s mother, became a target for the local Black Shirts. It was time to leave.

Sam, his sisters Josephine and Paula, and his mother arrived in New York harbor on October 3, 1929.

“…The first things my father told us were to be proud of our heritage, be loyal to America, be the best citizens possible and learn English as quickly as possible… »

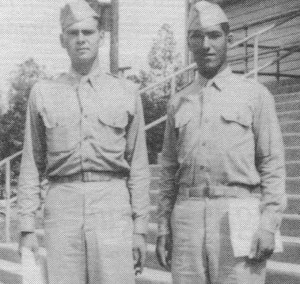

Graduation day at Fort Benning, GA. 2Lt Sam Lombardo (right) is pictured with classmate William McCLure. 2Lt McClure will be killed in Normandy.

On November 11, 1939, Sam volunteered for the 110th Infantry Regiment, part of the Pennsylvania National Guard. When the unit was called in federal service in 1941, Sam was a staff sergeant. His leadership abilities opened the doors of the OCS (Officer Candidate School) where he graduated on July 14, 1942. Assigned to Camp Robinson, Arkansas, then to Camp Fannin, Texas, to teach infantry basic training, Lieutenant Lombardo finally got his overseas assignment. In October 1944, he joined Company I, 394th Infantry Regiment, as platoon leader and fought with the company throughout the Battle of the Bulge.

After six months in combat, Sam hadn’t seen an American flag.

“…For the first time I had time to think about something other than fighting. I missed America, my home, my family and our flag. After all, our flag represented everything that was dear to me. I called Captain Morris, my CO, and requested that a flag be issued to us for display in the field. He forwarded my request to the headquarters. It was denied. The denial made me so furious that I thought to myself ‘If they won’t give us a flag, we’ll make one’. When I mentioned my idea to the men, all got as enthusiastic as I was …”

The 394th Infantry continued its advance eastward into Germany. After crossing the Erft Canal, Lombardo’s company arrived in the town of Mullenberg.

“… the town was the biggest display of white surrender flags I had seen to date. White flags were hanging from all windows. I was informed that we would spend the night there and thought why not to start our flag now. I brought some of my men around me and told them what I wanted to do. All were very happy and volunteered for the different tasks…”

One surrender flag became the base. In a nearby house, two large red pillows and a set of long blue curtains were ‘liberated’. As by miracle, a sewing machine materialized and all began to work feverishly, cutting white stars and red stripes. The project was well on the way. Lombardo and his men worked on the flag each time the company stopped and within a couple of weeks one side was done. Platoon guide, Sgt Bill Junod, was appointed caretaker, and he carried the flag in a little canvas pouch.

“… the next morning I told Sgt Junod, to bring the flag out. Even half finished, we displayed it over a window sill with its white background against the wall. We soon had many GI’s from other companies as well as ours come by and swell with pride looking at our flag. Morale was up, just as the troops got a glimpse of Old Glory …”

It took two and a half months to complete the 48-star flag, and it was finished just before the end of the war. After VE-Day, the company stayed in Germany for occupation duty before receiving new assignments. Men were reassigned daily, and Lombardo’s platoon was about to be disbanded. One morning, conducting the usual platoon roll call, Sgt Isadore Rosen informed his Lieutenant that the platoon had something for him.

“… Sgt Junod stepped out from the end of the platoon formation, came up to me and presented me with our flag. I was moved so much that I was at loss for too many words …”

Kitzingen, Germany, May 1945. 1st Lt Samuel Lombardo and platoon members displaying the flag for a US Army photograph. Back Row: L to R: Pfc. Gordon Wetherby, Charlestown, NH; T/Sgt Isadore Rosen, Pittsburgh, PA; Pfc. George E. Bellaire, Dayton, OH; 1st Lt. Samuel Lombardo, Altoona, PA

Front Row: Left to Right: Corp. Cury Beauvais, Chicopee Falls, MA; S/Sgt William Junod, Wyandotte, MI

First Lieutenant Samuel Lombardo came home in December 1945. He would continue to serve through the Korean War and the Vietnam War and eventually retired as Lieutenant Colonel. He lives today in Florida.

“… I was really dismayed when the Supreme Court ruled that burning or desecrating our flag was all right because it is an expression of free speech. I still don’t agree with their decision. Expression of free speech involves only the individual, but when one desecrates the flag in any way, it is trampling or destroying something that belongs to all of us. It gives me great satisfaction that my men and I made “our” flag. It is today protected at the Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, Georgia. At least this is one flag no one will burn or desecrate.”