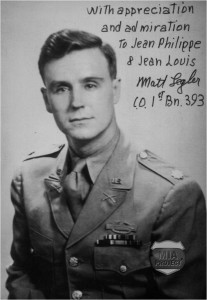

Prior to December 16, 1944, the 1st Battalion, 393rd Infantry held positions at the eastern edge of the Krinkelt Forest, with the battalion’s three infantry companies deployed along the Belgian-German border. The battalion commander was Major Matthew L. Legler, a 1939 West Point graduate.

On the first day of the “Bulge”, German attacks pushed back the frontline companies. They regrouped around the battalion command post deep in the forest. When withdrawal orders were issued, the battalion’s escape route was nearly closed., Major Legler decided to move out cross country. They eventually joined a sister battalion, the 2nd Battalion, 394th Infantry, and left the forest together. After failing to reach the village of Mürringen due to German troops there (see Withdrawal through Mürringen in War stories), the mixed group veered west. They decided to follow a creek running east-west between Krinkelt and Mürringen and then onto Wirtzfeld, which was reportedly still in American hands.The creek valley was a mile long and an easy walk on a sunny summer day but certainly not on a dark winter night. Small groups began to move on, sloshing through the mud and water, sliding and falling down, grabbing brushes and small trees.

Distant booms suddenly reverberated in the night. Artillery rounds poured down from the black sky. These were 155-mm shells fired by American guns, the retreating column having been mistaken for Germans. The hapless GIs had no place to hide or seek cover. Big explosions shook the valley, tearing, decapitating, and unmercifully cutting flesh. As medics bandaged the wounded and delivered morphine to the dying, others fled from the creek. The shelling split the column into small groups, each trying to escape the slaughter. Some of those who managed to get away reached a friendly outpost and sent a message to the artillerymen. The shelling stopped. Dazed and shocked, the survivors slowly emerged from the valley and continued westward.

Each battalion had about 800 men on December 16. Seventy-two hours later, when they reached the Elsenborn heights beyond Wirtzfeld, Major Legler’s battalion had less than 250 men. The 2nd Battalion, 394th was in a better shape with about 550 men and officers.

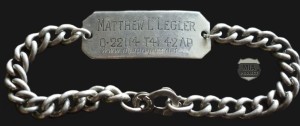

In November 1984, Legler’s identification bracelet came to light in the remains of a badly deteriorated wool overcoat recovered about fifty yards from the creek. Surprisingly, the overcoat also yielded two M1 rifles. It became apparent that the coat and rifles had been put together to make an improvised litter.

In November 1984, Legler’s identification bracelet came to light in the remains of a badly deteriorated wool overcoat recovered about fifty yards from the creek. Surprisingly, the overcoat also yielded two M1 rifles. It became apparent that the coat and rifles had been put together to make an improvised litter.

In 1989, Matt Legler returned to Belgium with a group of 99th Division veterans. During an evening reception at the Hotel Dahmen, Seel and Speder mentioned they had with them a sterling-silver bracelet that belonged to someone in the audience. The dining room fell silent. Applause followed after they announced the name. Legler stepped forward. With a broad smile, he put the bracelet around his wrist. “It still fits,” he said to the audience. He then removed the object and handed it back to Seel. He added, “But its rightful place is in your collection.” That sparked another ovation from the crowd. Legler well remembered the bracelet. His first wife had given it to him when he went  overseas. The couple had long since divorced, and the bracelet held no sentimental value. Legler couldn’t imagine how it ended up in the pocket of an enlisted man’s overcoat.

overseas. The couple had long since divorced, and the bracelet held no sentimental value. Legler couldn’t imagine how it ended up in the pocket of an enlisted man’s overcoat.

In early February 1945, Major Legler led his battalion in an attack to reduce the German presence on the Elsenborn Ridge when he stepped on a landmine. He was evacuated with facial injuries and a shattered foot and hand. The severity of his wounds ended his career, and he received a medical discharge in October 1945 with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He began a 34 year career with Mobil Oil Co in upstate New York. He retired in 1980 as Chief Motor Vehicle Design Engineer and moved back to South Carolina.

In the mid-1980s, a souvenir hunter found Major Legler’s West Point ring on the battlefield, presumably where the landmine wounded him. The ring was returned to its original owner and now resides in the Hall of Fame at the United States Military Academy.

Matthew Leon Legler passed away on June 23, 2012, at age ninety-six. He died in his home at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. On November 19, 2012, he found his final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 36A, Grave 439.