On battlefields, relics often surface decades after the battle. This is mainly because older generations kept the items as souvenirs or because local residents found practical applications for them. Here is a fascinating story revealed by the discovery of an old army bag.

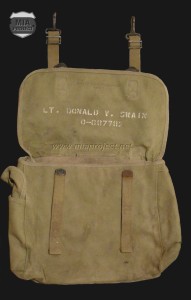

This bag, “Musette Bag M1936,” according to U.S. military specifications, surfaced in an old house in the vicinity of LaGleize, Belgium. The village is well known for having been the scene of hellish combat during the Battle of the Bulge. Beside an unusual rubberized texture, the musette bore the owner’s name and serial number: Lt Donald V. Swain 0-687782. This type of bag, often carried by airborne soldiers, was thought to be from an 82nd Airborne trooper since that unit saw heavy action in the

This bag, “Musette Bag M1936,” according to U.S. military specifications, surfaced in an old house in the vicinity of LaGleize, Belgium. The village is well known for having been the scene of hellish combat during the Battle of the Bulge. Beside an unusual rubberized texture, the musette bore the owner’s name and serial number: Lt Donald V. Swain 0-687782. This type of bag, often carried by airborne soldiers, was thought to be from an 82nd Airborne trooper since that unit saw heavy action in the area. The MIA Project’s database revealed that Lt Swain’s name was inscribed on the Tablets of the Missing at the Ardennes American Cemetery. The date of death was puzzling – May 28, 1944, four months before the liberation of Belgium! A call to the cemetery confirmed the date and shed light on the former owner’s whereabouts. Donald V. Swain was a B-17 crew member of the 751st Bomb Squadron of the 457th Bomb Group. The MACR (missing air crew report) added more information. The B-17G serial 42-97452 was lost at sea with all its crew after a bombing mission over Dessau, Germany, on May 28, 1944. The information was interesting but didn’t answer two questions. What happened that fateful day and how did the bag end up in Belgium?

area. The MIA Project’s database revealed that Lt Swain’s name was inscribed on the Tablets of the Missing at the Ardennes American Cemetery. The date of death was puzzling – May 28, 1944, four months before the liberation of Belgium! A call to the cemetery confirmed the date and shed light on the former owner’s whereabouts. Donald V. Swain was a B-17 crew member of the 751st Bomb Squadron of the 457th Bomb Group. The MACR (missing air crew report) added more information. The B-17G serial 42-97452 was lost at sea with all its crew after a bombing mission over Dessau, Germany, on May 28, 1944. The information was interesting but didn’t answer two questions. What happened that fateful day and how did the bag end up in Belgium?

A member of the 457th Bomb Group Association provided the key to the mystery. Jack Gumm, co-pilot aboard Lieutenant Auld’s ship, recalled:

“…Swain had graduated from the Air Force Cadet training base in Ft Sumner, New Mexico, and we met just after at Ephrata, Washington, where we had joined the 457th. The first pilots had all had some training with B-17s. Swain and others who graduated with us were assigned to the group as co-pilots. We trained in Ephrata for a few weeks and were sent to Rapid City, SD, and took extensive training there. Afterward, we went from there to Wendover, Utah, for our final training phase. We were also assigned new B-17 bombers. We then flew the planes to England via Gander, Newfoundland, Iceland, and then Glatton, England …”

The first aircraft arrived at Glatton on January 17, 1944, and the group flew its first combat mission on February 22. On May 28, 1944, the 457th flew mission number fifty-three. There were multiple targets, all related to the Junkers aircraft works at Dessau, Germany. The flight was uneventful until the different elements of the 457th took separate courses toward their different objectives. On the approach to Dessau, the 457th encountered a mixed force of fifty to sixty Me109s and FW190s, and several ships went down. After the bomb run, and just as the formation departed for home, the craft piloted by Lieutenant Emmanuel Hauf sustained a Flak hit which set the right wing on fire. The damage to the wing was noticeable as it was on the leading edge and on the top surface, but the plane remained in formation. Over Belgium the plane began lagging behind and losing altitude.

Jack Gumm continued: “I am probably the last man to talk to Lt Swain. He was the co-pilot in Hauf’s plane. As usual co-pilots handled the radio communications. Hauf and our crew were in the same formation that day. … Hauf and Swain were flying just above us. They got a direct hit in the right wing tank and the gasoline caught fire. The B-17 had neoprene lined gas tanks. If one was punctured, it was supposed to reseal itself. The shell that hit Hauf’s plane exploded in the tank and made a hole too big to seal. At first there was quite a large flame and then the seal partially closed the hole, and the burning slowed. From our position in the formation I had a good view on the burning tank. We were at 22,000 feet, and, in the rarified air, the gas didn’t burn too well. Hauf and Swain talked to me and my first pilot about whether to bail out or not and we discussed the best course of action. Hauf had his crew on alert to bail out over Germany but decided to stick with the formation. When we were close to the Belgian coast, our formation started to descend to 15,000 feet over the Channel. The fire in the tank immediately increased, and we told Hauf. He decided not to bail out until he reached England. About 40 K’s from the English coast, the wing gave way and folded back. The B-17 went into a rapid flat spin. The centrifugal force was probably too great for the crew to bail out. We pulled out of formation and followed the plane all the way to the surface of the Channel. It sank immediately and no bodies were seen. We circled the area about five minutes, but no bodies came to the surface. …”

Though the circumstances under which the musette bag ended up in the LaGleize area will never be known for certain, it’s reasonable to assume that the crew of Hauf’s ship discarded excess gear to help keep their machine aloft, and the bag probably was among the items falling from the clouds. Beside Swain’s name, which sparked the research, the bag also brought back to light eight other forgotten names. The ill-fated crew remains lost at sea, never to be recovered. Their story had to be told.

B-17G serial 42-97452 (no known nickname) – 751st B.S, 457th B.G.

Lt Hauf’s crew pictured on May 22, 1944 after the Kiel mission. Lt Donald V. Swain is standing, third from left.

Lt Hauf’s crewmembers were:

1/Lt Emmanuel Hauf – pilot

2/Lt Donald V. Swain – Copilot

2/Lt William R. Hawley – Navigator

2/Lt Richard E. Jaqua – Bombardier

T/Sgt Willis H. Johnson – Aircraft Engineer & top turret

T/Sgt James J. Kilroy – Radio Operator

S/Sgt Paul R. Moore – Waist gunner

S/Sgt Walter Furtta – Ball turret gunner

S/Sgt Oscar A. Gascon – Tail gunner

Photographs courtesy Jack Gumm