The 99th Infantry Division Air Section

Escape from Büllingen

by JP Speder

Wars in the skies have been glamorized in many ways for propaganda purposes, to sell war bonds or to promote a life full of adventures and glory. But there were no foxholes in the skies, no place to hide and the brutal reality never appeared in the news. Far from the glory of fighter aces, less heroic and much below in altitude than bomber crews, there was a group of pilots who flew missions almost anonymously only armed with a pair of binoculars and a cal .45 pistol. No roaring names such as “Mustang”, “Lightning” or “Blackwidow”, they were the « Grasshopers ».

Those unsung heroes were Piper Cub pilots. Flying L-4 observation planes, they played an equally important and equally dangerous task than their big brothers. They assured accurate artillery fire and provided first hand observation of the front lines. They were the eyes of their division.

Camp Maxey – Air Section barrack (left) and Air Section members at rest ( Courtesy Joe Weckerle)

Commanded by Major Howard E. Cunningham, the 99th Infantry Division artillery air section was constituted of ten L-4 observation planes. Two for each of the field artillery battalions and two for division field artillery headquarters. The latter however had three pilots—the commander, his assistant commander – Captain Joseph C. Weckerle, and Lt Robert W. Keans. So there were eleven pilots for the division air section, plus air observers, ground crew and a kitchen section. When the 99th Division was deployed on line early November 1944, all the planes and crews were stationed at the same landing strip at the south west corner of the town of Büllingen, Belgium.

Lt Charles E. Whitehead, air observer with the 370th Field Artillery Battalion remembers the arrival in Belgium.

“… Our pilots picked-up the planes in England and flew them across the channel to Lille, France. Then they flew them to Bullingen, Belgium. When they arrived I left the battery at Krinkelt and went to the air section at Bullingen as an aerial observer. Each of the battalion pilots flew at least one mission a day if possible. We tried to have at least one plane in the air at all times. I was the only observer for the 370th so I flew with both pilots…”

Büllingen was no sleepy place like all the other villages in the area. As the largest and closest town to the front lines, Büllingen was a rear base and hosted ammo, ration or gas dumps for many units in the immediate neighborhood. The 2nd Infantry Division Air Section also had all its L-4’s parked on a strip just next the 99th with two more Cubs of the 16th Armored Field Artillery Battalion of CCB, 9th Armored Division.

“…My training to be an observer was two 1-hour flights with Chuck Proctor, before we left the States…” continues Charly Whitehead “… So, this third time I flew, we were in combat. The weeks before the Bulge were routine and sometimes down right dull. The weather to fly was miserable. There was lots of overcast, low ceiling days with fog every once in awhile. Some days we would only get 2-3 missions flown, some days none. The ground got so soft we had trouble getting up to flying speed. Capt. Weckerle took a drive to an air force base and brought back about 300-ft. of metal grating. We put this down and were able to get up to speed from then on…”

Pilots of the 99th Division Air Section (courtesy Joe Weckerle) Capt Weckerle is standing far right.

“… Saturday December 16th, 1944 was foggy and damp. Since I hadn’t been back to Battalion for awhile, I was selected to go. After picking up our rations, and visiting a little, I went to check with Col. Brindley to see if he wanted the air section to do anything for him. He told me division had sent out a bulletin of a [German] armored patrol behind our lines and we should post a double guard. When I got back to Bullingen I found out the weather had cleared enough that Chuck Proctor and Bruce Sears had tried to fly a mission together. The Germans were sending the V1 rockets at such frequent intervals that they had spent most of the flight trying to dodge the anti-aircraft being fired at the rockets. They were aware that there was increased activity along the front, but couldn’t get high enough for the period of time it took to fire the Battalion. After lunch Bruce and I tried to get to the front; but the fog had moved in just about the treetops and we couldn’t see anything…”

Unknown to the Americans stationed in Büllingen, the armored spearhead of the 1st SS Panzer Division commanded by SS Colonel Peiper had breached the front lines and was progressing toward the town.

“… About 4 AM, Sunday December 17th, one of our radiomen who was monitoring the division radio channel picked-up a report of German tanks in a village near us. It was suggested we pack and be ready to move. At about 7 A.M, Proctor told me to see if the cooks could fix us something, and as soon as it was light we would take off for the front. I went downstairs and was startled to find the kitchen gone. I found Caldwell, one of the cook, and was said everyone was loaded and leaving. I ran outside, found S/Sgt Watts in the column, told him to wait. We got bed-rolls, etc. and tossed them in his jeep and he took off after the tail of the column…”

At the same moment, near the strip, the leading German armored vehicles had reached a road block hastily established by men of Service Battery of the 924th Field Artillery Battalion. A brief and violent fire fight erupted. It didn’t last long until German SS Grenadiers and half tracks broke through and entered the town. Meanwhile at the air strip …

“…We trotted out to the airfield, all the other pilots had taken off … Sears’s plane was closer, so I helped him start his Cub. The Cub had no electrical starter and had to be started by someone pulling the propeller thru a cycle till the engine started. Proctor was several yards away and Sears told me to help Proctor. As I ran down to help Proctor, bullets were cutting limbs from the trees around us. I got the Cub started and I got in. We taxied a few yards and the plane got stuck in the mud. I had to get out and push the plane to get it rolling. Proctor taxied to solid ground, stopped and waited for me to catch up. As I got my foot on the step, he opened up the throttle and we went bouncing over the field with me half in and half out of the plane. Remarkably, all the while he was stationary waiting for me not a single shot was fired. By the time I got into the seat, the door closed and buckled in, we were almost up to flying speed. As soon as we were off the ground Proctor climbed just above the trees and ducked into the hollow to our north flying at treetop level. We didn’t try to get to our metal grating to take off and that was very fortunate for there was a German half-track approaching at the far end of it and had begun firing. To the best of my knowledge, we were the last plane to leave. When we got airborne, we joined Sears and Tadlock’s planes. …”

The three planes flew to an air strip at Spa. After reporting their encounter with the German tank column to a 1st US Army officer, they were told that as a green outfit they were spooked and should go back to Büllingen. The three pilots thought everyone was supposed to go back to Spa but instead might be at the auxiliary field near Malmedy. The decided to fly back from Spa to Malmedy and indeed found the rest of the 99th air section. They found out that nine of the ten planes had escaped. The only one abandonned was Capt Weckerle’s. Joe Weckerle had been grounded after being injured in a truck wreck in England and was not on flying status. He had taken the lead of the vehicle column that left Büllingen.

Original Grasshopers leather patch worn by Capt Weckerle during all his service with the 99th Air Section (MIA Project collection – donated by Joe Weckerle via Joe Keirn)

After gathering at Malmedy, the 99th Division Air Section flew back to Spa to the 1st US Army HQ, which by the time had taken full measure of the German offensive and was leaving the town. The next day, they flew to Eupen, rear base of the Vth US Corps. They were finally able to establish contact with the 99th Division Headquarters near Elsenborn and within a few days were again flying missions for the division.

AII nine pilots, who flew out of Büllingen received the Distinguished Flying Cross during an impressive ceremony held in Kitzingen, Germany in May of 1945. It was covered by the Stars & Stripes. The article read :

“This is the only division of the Armies of the United States in which all its liaison pilots have been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross”. These were the words of Maj Gen Walter E. Lauer, Commanding General of the 99th Division as he awarded the DFC medal to all nine of the liaison pilots of the division in an impressive ceremony which took place at the 99th division CP in Kitzingen. Before an array of troops representing each of the Infantry Regiments (393rd, 394th and 395th), Gen. Lauer , along with Brig. Gen. Frederick H. Black, commanding general of the 99th Division Artillery and Brig. Gen. Hugh T. Matberry, assistant division commander, honored the nine pilots.

“This is the only division of the Armies of the United States in which all its liaison pilots have been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross”. These were the words of Maj Gen Walter E. Lauer, Commanding General of the 99th Division as he awarded the DFC medal to all nine of the liaison pilots of the division in an impressive ceremony which took place at the 99th division CP in Kitzingen. Before an array of troops representing each of the Infantry Regiments (393rd, 394th and 395th), Gen. Lauer , along with Brig. Gen. Frederick H. Black, commanding general of the 99th Division Artillery and Brig. Gen. Hugh T. Matberry, assistant division commander, honored the nine pilots.

Receiving the medal were Lts Robert W. Kean, Jr, Herbert B. M. Sears, William J. Little, Charles L. Proctor, J.C. Gaston, Orin A. Lehman, John M. Hilson, James W. Ramsey and Max R. Tadlock. Decorated with the Silver Star at this same ceremony was Maj. Howard E. Cunningham in charge of the 99th air liaison section, whose supervision of the section made it one of the smoothest running and efficient in the Army.

Sources:

Charles Whitehead memories.

Conversations with Joe Weckerle and Joseph E. Keirn

Information and photos from the Cunningham family

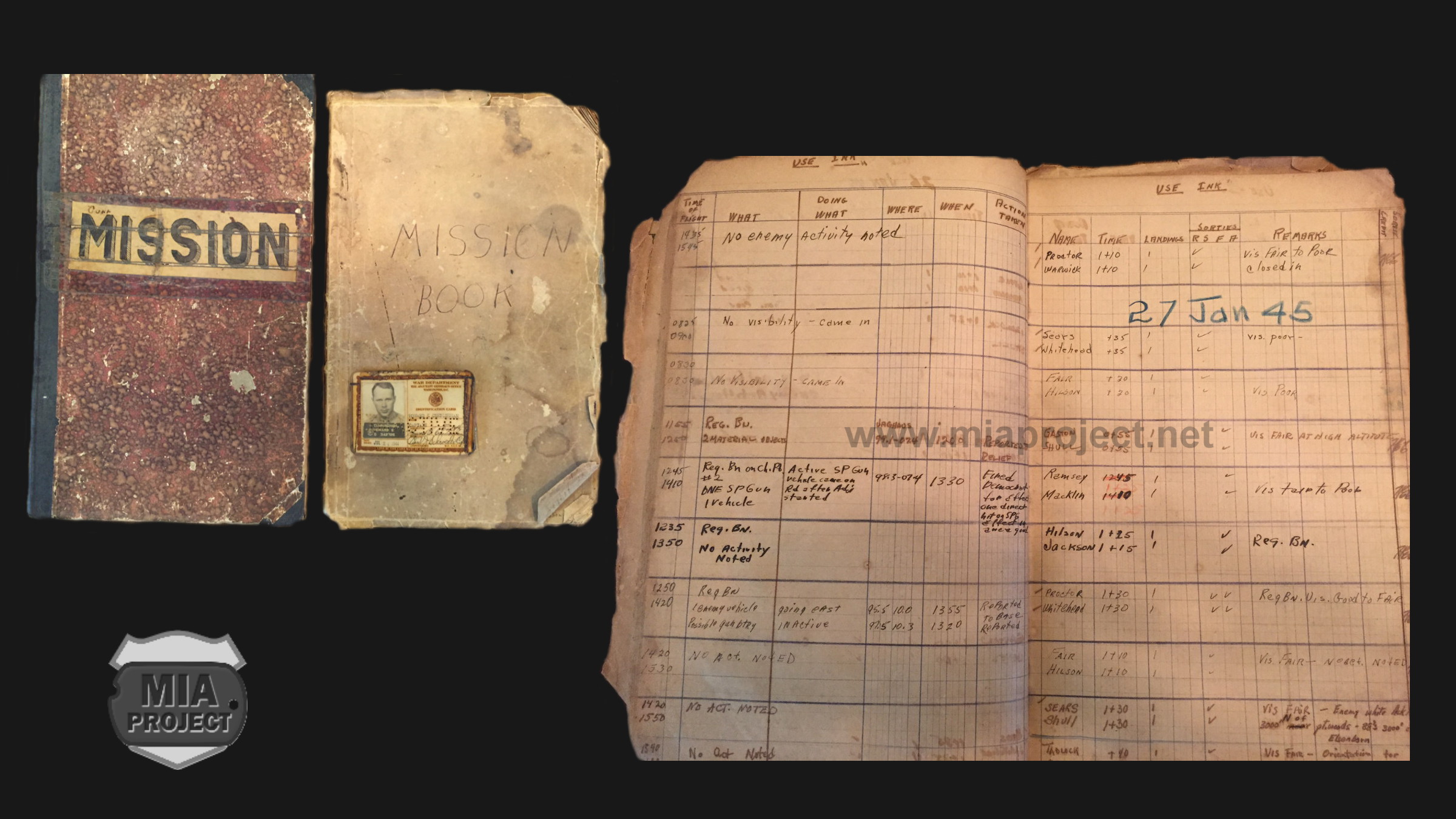

MIA collections