By JP Speder

Sources:

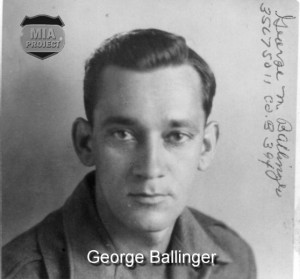

Interviews and correspondance with George Ballinger

Interview and correspondance with Robert Muyres

Alphonse Sito – IDPF

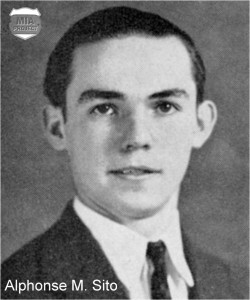

PFC Alphonse M. Sito

Baltimore, Maryland

Company B,

394th Infantry Regiment

I. Historical background

Losheimergraben, December 16, 1944.

Standing behind a decapitated tree, the German scout cautiously peered through the morning mist. The recent artillery barrage had slashed many trees, and it was difficult to make out the American frontline. There was not a sound in the forest other than the distant rumble of artillery.

Less than fifty  yards in front of the scout, on a slight rise, S/Sgt George Ballinger was observing the German soldier. Ballinger’s machine-gun section had arrived three weeks earlier and was occupying a little knoll in the heart of the thick forest. It was so dense that daylight seldom reached the men. Dampness and ground haze were their constant companions. They dubbed the place “Creepy Corner.” From their position, the Americans looked down on a small ravine, and, despite a limited field of fire, they acted as gatekeepers for the left flank of Company B, 394th Infantry.

yards in front of the scout, on a slight rise, S/Sgt George Ballinger was observing the German soldier. Ballinger’s machine-gun section had arrived three weeks earlier and was occupying a little knoll in the heart of the thick forest. It was so dense that daylight seldom reached the men. Dampness and ground haze were their constant companions. They dubbed the place “Creepy Corner.” From their position, the Americans looked down on a small ravine, and, despite a limited field of fire, they acted as gatekeepers for the left flank of Company B, 394th Infantry.

The German scout disappeared. He soon returned with a small group of grenadiers. Behind his machine gun, PFC George Boggs was ready to fire, but Ballinger told him to wait. Within minutes a larger group appeared. The Germans were talking and seemed unaware of the American presence. As they started to set up a machine gun on a tripod, Ballinger looked at Boggs and nodded. Boggs fired a long burst and all the Germans fell. That seemed to be the signal for everybody to start shooting.

German troops began to assault Ballinger’s thin defensive line from multiple directions. PFC Alphonse Sito was on his squad’s right flank with a BAR team. He was shouting above the deafening rifle fire, reporting German movements to Ballinger. They received intense machine-gun fire, and the Germans soon broke through. Sito’s last words to Ballinger were to report that the BAR team had been wiped out. An enemy bullet drilled Sito, and, with a jerk of his head, he fell backward in his hole.

The German fire was so intense and so low that it chewed apart the logs protecting Ballinger’s gun pit. Unable to return fire, there were only two options, surrender or die. Ballinger fastened a white undershirt to a machine gun cleaning rod and stuck it out the dugout opening. The firing instantly stopped. As the Germans marched away their captives, Boggs and Ballinger tried to care for Sito’s body, but their captors disapproved.

During the second week of the Battle of the Bulge, Alphonse M. Sito was reported missing in action, and his status remained unchanged at war’s end. In 1951, the army officially closed his case, declaring his remains non-recoverable.

II. A chance discovery

The area where Sito died was several hundred yards inside Germany. Access to the forest had to be made through a customs checkpoint, manned, at the time, by Belgian and German customs police. Despite the potential risk of crossing the border with metal detectors, Seel and Speder had decided to explore the German side of the border, known to be the bloody battleground of the 1st Battalion, 394th Infantry.

On September 27, 1988, the two young Belgians drove across the border and slipped into the thick forest with their metal detectors. It didn’t take long to find the first rusty vestiges of war, shell fragments and small-arms ammunition. Seel and Speder eventually chanced upon a line of American foxholes. Grenades, rifle clips, and ration cans soon surfaced. The area was almost untouched since the war. As the day wore on, they decided to come back again two days later and resume the search.

On September 29, the pair returned. The line of foxholes extended to the edge of a small ravine. At this location the conifers were young and dense. So dense they nearly prevented access to that section of the forest. The two men made their way inside and came to a cluster of dugouts. More equipment surfaced. In a slit trench, Seel began to unearth a German mess kit, then K rations, toothbrushes, and a shaving razor. As he dug down, he found a half rotted overshoe. He looked inside and discovered a leather shoe filled with small bones. Speder who was a few yards away joined his friend, and they began to carefully excavate the trench, convinced they had found the remains of an American soldier. After several hours, they had recovered most of the skeleton. The shattered skull showed evidence of a head wound. And there were brass dog tags around the cervical vertebrae. The tags bore the name Alphonse M. Sito.

Along with the bones and dog tags, Seel and Speder discovered Sito’s wallet, coins, a comb, a cigarette lighter, American uniform shreds, a PFC stripe, rosary beads, a pocket missal, a plastic prayer card, two plastic crucifixes, and a well preserved piece of white silk. The four-inch square silk artifact turned out to be a Christmas greeting. It had a holiday decoration and the words “To One I Love.”

Along with the bones and dog tags, Seel and Speder discovered Sito’s wallet, coins, a comb, a cigarette lighter, American uniform shreds, a PFC stripe, rosary beads, a pocket missal, a plastic prayer card, two plastic crucifixes, and a well preserved piece of white silk. The four-inch square silk artifact turned out to be a Christmas greeting. It had a holiday decoration and the words “To One I Love.”

III. USAMAA-E

The discovery of Alphonse Sito’s grave presented a complicated situation. Two Belgians had found the remains of an American soldier in Germany. The Belgians wished to avoid legal trouble and sought help from a British author and historian living in Belgium. Will Cavanagh was a Battle of the Bulge researcher and had many contacts within the U.S. Government. He phoned a friend who worked for the American Battle Monuments Commission. The friend notified the director of the U.S. Army Memorial Affairs Activity Europe (USAMAA-E) located at Frankfurt, Germany.

Michael Tocchetti was USAMAA-E director. He and a member of his staff drove to the discovery site and verified the find. Tocchetti returned a week later with a recovery team and excavated the site. They took possession of the remains and artifacts and transported them to Frankfurt. He later transferred everything to the Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii (CILHI).

The scientific staff at CILHI positively identified the remains. The army then traced Sito’s family in Baltimore. His oldest brother Stanley was the point of contact. The funeral of Alphonse Martin Sito took place on December 18, 1989, at St. Stanislaus Cemetery.

The discovery of Sito’s remains became the inspiration for the 99th Division MIA Project.