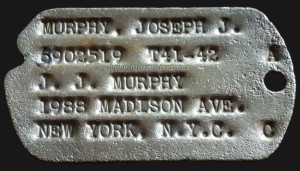

This dog tag was recovered in a heavily wooded sector north of Rocherath, known as being a no-man’s-land in October-November 1944.

This dog tag was recovered in a heavily wooded sector north of Rocherath, known as being a no-man’s-land in October-November 1944.

The former owner was immediately located. Sgt Joseph J. Murphy was killed in action on October 28, 1944, and was buried in the US Military Cemetery of Henri Chapelle, Belgium. He was serving with Company B of the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion.

The circumstances surrounding his death are dreadful.

First Lieutenant Wesley Ross, his platoon leader, recalls:

« … Formal anti-personnel minefields were recorded in great detail, so that they can be precisely located at any time. The small non-formal minefields, that caused many of our casualties, were ones that were scattered around as perimeter defenses by our infantry, or were used to deny access along obvious approach avenues. These were to be removed when the laying unit moved out of the area. Often, these mines were imprecisely located on crude hand-drawn maps, making them extremely hazardous to locate on the ground.

« … Formal anti-personnel minefields were recorded in great detail, so that they can be precisely located at any time. The small non-formal minefields, that caused many of our casualties, were ones that were scattered around as perimeter defenses by our infantry, or were used to deny access along obvious approach avenues. These were to be removed when the laying unit moved out of the area. Often, these mines were imprecisely located on crude hand-drawn maps, making them extremely hazardous to locate on the ground.

Near Kalterherberg, our « B » Company took over one of these minefields from an engineer outfit that had moved out on short notice, without being allowed time to go over their layouts. Our first casualty was a sergeant from the first platoon who tripped one of their home made mines — spikes wrapped around several sticks of dynamite. He had more than fifty fragments in his body, including five through his liver and stomach. Miraculously he survived but he never returned to the 146th.

Several days later, Sgt Joe Murphy saved me from a similar fate by spotting a tripwire just as I nudged into it. The crudely penciled map seemed to show the mine about 60 feet ahead. Murphy had dropped to the ground in an attempt to spot the trip wires. Our trip wires had splotches of green and brown camouflage paint on bare steel. When exposed to the elements, the unpainted areas rusted, resulting in a very effective camouflage pattern that was difficult to see when looking down toward the ground but much easier to see against the sky. Murphy yelled « STOP », and just as I turned and looked back, I felt the trip wire through the double-layer of my tanker coveralls. I was that close to disaster! This was another spikes and dynamite affair that was waist high in a fence about 25 feet away.

Murphy had come from the 5th Division in Iceland, and had joined us in France as a replacement. He was a fiesty little Irishman, daring but foolhardy, and he took so many chances that his squad members preferred not to be around him when mines were being handled.

He was killed a few weeks later when one of our A.P. mines exploded in his face as he was attempting to arm it. He probably pulled the safety pin while there was still tension on the trip wire — a definite no-no. I too was at fault, because I had allowed him to tie a lateral trip wire on the main trip wire — a breach in mine laying technique to which Sgt Homer Jackson had objected at the time.

There was a deadly silence as the small fir tree which had supported the mine was cut in two by the blast and fell over on the ground.

I ran up but could do nothing, as several of his main internal arteries were severed. He died without regaining consciousness. For several ghastly minutes I listened to the « swish-swish-swish » as his blood squirted out internally with each heartbeat; really a horrible sound in a completely hopeless situation. We carried his stiff body back to the graves registration unit the following morning… »